Saint-Gaudens, Zorn, and the Goddesslike Miss Anderson

by William E. Hagans

The article first appeared in the summer 2002 issue of American Art

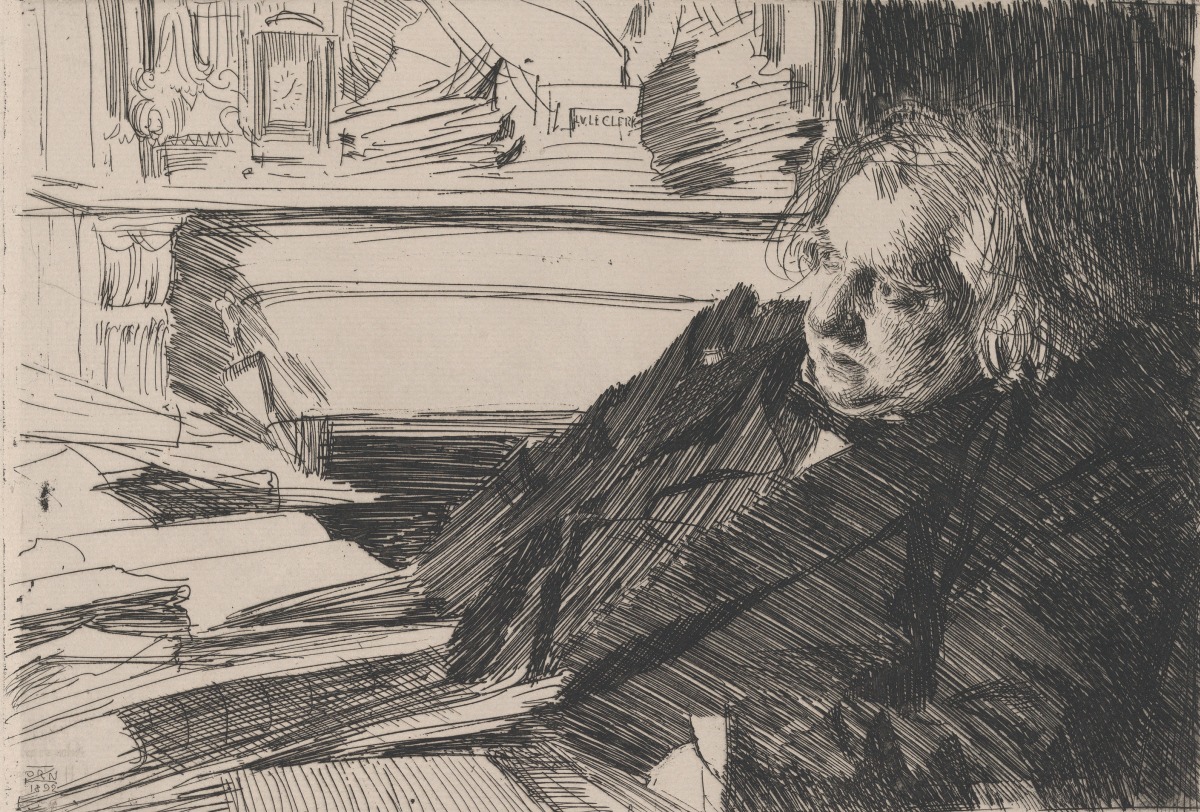

Swedish artist Anders Zorn (1860-1920) etched a portrait of Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848-1907) and his model while visiting the sculptor's New York City studio on February 14, 1897. This diminutive work ranks alongside Zorn's etched portraits of Ernest Renan, Madame Simon, Paul Verlaine, and Auguste Rodin as one of the artist's finest character studies. The image also provides an important entrée into the entwined personal and professional relationship of Zorn and Saint-Gaudens. Although there has been confusion regarding the identity of the nude woman positioned behind the sculptor in the print, recent research has identified her as Harriette Eugenia Anderson, also a model for the Victory of Saint-Gaudens’s Sherman Monument and the twenty-dollar gold coin that he designed for the United States Mint. 1

Zorn probably met Saint-Gaudens in 1893 when he made his first trip to the United States to attend the Chicago World's Fair. Having lived in Paris for the previous five years, Zorn knew a number of expatriate American artists, including John White Alexander, Paul Wayland Bartlett, and Saint-Gaudens's protégé, Frederick MacMonnies. Even though Zorn was also linked to French artists Albert Besnard and Auguste Rodin, having joined them in the breakaway Salon du Champ de Mars after the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris, he wrote in his memoirs, "My countrymen and other Scandinavians, along with Americans [in Paris], were the closest and the most sympathetic [to my work]." 2

Elizabeth Alexander, wife of John White Alexander, wrote of Paris in the early 1890s: "At the time Scandinavian painters were very much in the eye of the public... The work of Zorn, Frits Thaulow, [Peder] Kröyer, and a number of others had been shown in nearly every exposition on the continent... They were all living and working in Paris at the time. We found the life there more than interesting because of these contacts. We were at home on Saturday evenings if we were in Paris and there was never a Saturday that some interesting person did not walk in. Life in Paris was in those days so different from life in New York–men had no clubs and used the studios instead." 3

An influential trio of Americans in Paris encouraged Zorn to participate in theColumbian World Exposition, also known as the Chicago World's Fair. Halsey Ives, who would head the Department of Fine Arts at the fair, had encountered indifference about it on the part of Swedes during a trip to Europe. Thus he saw Zorn, a well-known Swedish artist who wanted to travel to America – over twenty percent of the population of his hometown of Mora had emigrated from Sweden to the United States – as a logical candidate for Swedish commissioner of art for the event. Sara Hallowell, who Zorn sketched, would serve as an assistant to Ives at the fair and was instrumental in procuring artwork for her wealthy clients, such as Berthe Palmer. Most likely with Hallowell's help, Palmer purchased Zorn's Little Brewery (1890) while in Europe.

When Anders Zorn and his wife, Emma, arrived in New York six weeks before the opening of the Columbian World Exposition, they were introduced to the members of the highest social stratum by insurance executive James Waddell Alexander and the banker Jacob Schiff. Zorn had established a reputation for himself in Paris by exhibiting annually at the salon. In addition, the recent success of his etching of French theologian Ernest Renan and the camaraderie with Americans abroad facilitated his admittance to America's art milieu. During his two-week stay in New York, Zorn arranged for an exhibition of his etchings at the Frederick Keppel Gallery on East Sixteenth Street. At the home of Henry Marquand, Zorn sketched the prominent businessman and generous benefactor, who was president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. 4

Zorn wrote of his visit to New York in his Memoirs: "Ah!, the first impressions of this world city were remarkable." In America, the Swede had found his element.

Born out of wedlock in the rural Swedish province of Dalarna, he embraced the less restrictive American culture:

"I get on well in America and with Americans. Their frank, straightforward manner suits my nature. I've never really been able to stand our urban Europeans' ceremonious style and artificial customs. When I first came out of Dalarna, I quickly learned that everything I knew and valued was considered nothing... But the only rules of conduct that were so severely impressed on me by my grandfather from my earliest childhood were not so tricky; faithfulness, being true to one's word, honesty, and punctuality, virtues I discovered were unnecessary in the cities of Europe... Why was I more than other foreigners during [my first visit to America] closest to the elite of America and introduced in all the clubs? Everywhere I go, I ascribe this to my grandfather, the splendid old Mora peasant who raised me until I was twelve... Over there [in America], when they say 'He’s all-right,' all doors open to the foreigner, which Europeans cannot understand. Openness, honesty, straightforwardness, punctuality, these things are included in the testimonial 'He’s all-right.'" 5

The Alexanders and Schiffs placed their carriages at the disposal of the Zorns and saw to it that they had access to concerts and the theater. On Good Friday, March 31, when there were few invitations to dinner because of the religious holiday, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, who had no compunction about entertaining then, invited the Zorns to dine with him. It was the beginning of a close friendship between the sculptor and the painter-etcher.

Homer Saint-Gaudens, the sculptor's son, wrote: "Zorn...was always a favorite with my father, [and] furnished many anecdotes which the sculptor recounted... The last of them was especially liked because of its illustration of the casual way Zorn took himself. The artist appeared at the studio one morning to sit silent for some minutes, as was his custom while my father worked.'What are you doing next?' said my father, finally breaking the pause without turning around. 'Going back to Europe in twenty minutes,' breathed Zorn without looking up. And he went." 6

Over the course of his professional life, Zorn enjoyed the company of both European and American sculptors. An expert woodcarver since childhood, Zorn attempted a number of sculpted works himself, most notably his monumental Gustav Vasa. For his Self-portrait (1889) in the Uffizi Museum in Florence, Zorn depicted himself as a sculptor working on a bust of his wife. In 1895, Zorn portrayed himself at work on his Faun and Nymph, a Rodinesque couple in a sensual embrace that he completed the same year. 7

Over the years, Saint-Gaudens and Zorn portrayed a number of the same sitters: Theodore Roosevelt, diplomat John Hay, first lady Frances Folsom Cleveland, philanthropist Frieda Fanny Schiff Warburg, lawmaker Marcus A. Hanna, and diplomat David J. Hill.

In another intersection, Saint-Gaudens also made a bas-relief in bronze of essayist Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer (1888), who wrote the first American profile of Zorn, "A Swedish Etcher", for the August 1893 edition of Century Magazine.

Zorn would have been interested, too, in an early work by Saint-Gaudens, the John Ericsson Monument (1873-74), which honored the Swedish naval engineer and inventor who helped develop the Union's Monitor naval vessel during the Civil War. Zorn painted a watercolor of the USS Baltimore (1890) steaming into Stockholm with the remains of Ericsson.

Further cementing the artists' professional relationship was their mutual association with the Columbian World Exposition, which opened on May 1, 1893. On his first of seven trips to America, Zorn not only sold all of his own work, he also renewed and forged relationships with important American patrons. He created a painting of Mrs. Palmer for the Woman’s Department of the fair and later etched her portrait. Collector Isabella Stewart Gardner purchased Zorn's Omnibus (1892) while visiting Chicago, and the following year she invited the Zorns to Venice, where Zorn painted her portrait. He also etched her likeness that year. In addition, Zorn sold The Waltz (1891) to George W. Vanderbilt. It hangs at the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina. Zorn met industrialist and amateur artist Charles Deering at the fair and spent the summer at Deering's Evanston home recuperating from a fall. Gardner and Deering, who became chairman of International Harvester in 1900, secured many portrait commissions for Zorn over the years.

In Chicago, Zorn met Daniel H. Burnham, chief architect at the fair; Maria Sheldon Scammon, founder of the lecture series at the Art Institute of Chicago; and Senators Nelson Alderich and Mark Hanna. Zorn painted portraits of each of these Americans in coming years. The Art Amateur declared, "We believe that if a vote were taken, Mr. Zorn would turn out to be the most popular artist with artists at the World's Fair." In a letter to her mother in Sweden, Emma Zorn summarized her husband’s triumph in Chicago: "If life continues as it has this year, I have reason to be grateful... Anders has had colossal success, so much more than we ever dreamed possible. It is as if by a stroke of luck he has become known by all in what is called the art world in America." 8

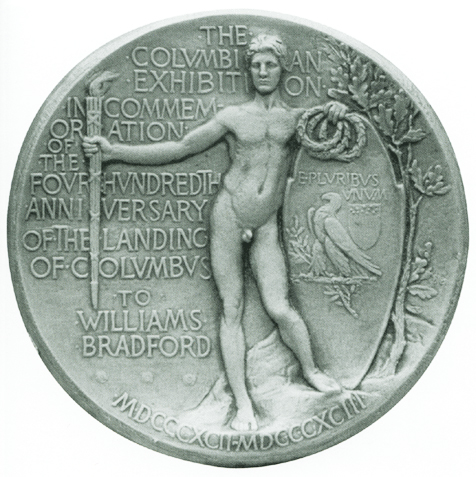

By 1893, Saint-Gaudens was one of America's most successful sculptors, with critical acclaim for his Farragut Monument (1877-80), Diana (first version, 1886), and Adams Memorial (1891). As did many of his colleagues, Saint-Gaudens saw the Chicago World's Fair as a defining moment for American art and architecture. Imbued with a uniquely American enthusiasm, he declared at one of the planning sessions, "This is the greatest meeting of artists since the fifteenth century!" However, his contribution to the fair was touched by controversy. He served as chief advisor for sculpture, but declined to produce original work, deferring to younger colleagues such as Daniel Chester French and MacMonnies. He did design, though, a presentation medal for award-winning artwork at the fair. On the obverse, he depicted Columbus in armor, with sword and cape; on the reverse, a nude youth. When this design was leaked to the press, the moral watchdogs in America attached it as inappropriate. Even though he revised it, the reverse of the medal was eventually replaced with a design by the United States Mint's chief engraver, Charles E. Barber. 9

When Zorn visited America for a second time during the winter of 1896-97 to paint portraits, both he and Saint-Gaudens were at another important juncture in their careers. Zorn intended to abandon his studio on Boulevard Clichy in Paris upon his return to Europe and to go back to Mora, about two hundred miles northwest of Stockholm. Later, he designed and supervised the building of his country estate, called Zorn Manor, next to Mora Church. The peripatetic Swede, at the age of thirty-seven, had finally found a permanent home. Zorn wrote in his memoirs: "There has never been a prouder homeowner. Having been born poorer than some and the legitimate heir to nothing, I was now the wealthiest. Exiled in foreign lands, the homeless now had a home for himself and his loved ones." 10

On the other hand, Saint-Gaudens was preparing to leave New York for Paris. In his memoirs, he recalled the noise of the newly built elevated railroad, the increased traffic, and the changing cityscape that alienated him from the New York he remembered before the Civil War. A victim of success, he was interrupted by admires, friends, and prospective clients and was years behind on several major commissions. Furthermore, he was supporting several studios with a number of assistants and two households–the New York home of his wife, Augusta Saint-Gaudens, and their son, Homer, and the Connecticut home of his mistress, Swedish-born Davida Johnson Clark, and their son, Louis Clark. Saint-Gaudens also had a large summer home and two studios in Cornish, New Hampshire, where he helped to found an art colony in 1885.

Several important monuments by Saint-Gaudens were unveiled in 1897, including an equestrian statue of General John A. Logan for the city of Chicago and the Boston memorial to Robert Gould Shaw and the soldiers of the Massachusetts Fifty-fourth Regiment, which many consider the sculptor’s masterpiece. He was also working on an equestrian monument to General William Tecumseh Sherman, destined for the southeastern corner of Central Park in New York City.

The winter of 1897 was a busy, difficult time for Saint-Gaudens. He wrote to his niece Rose Nichols, a landscape architect, about several sculptures in progress, the Zorn etching, and about the recent death of his close friend from student days in Paris, artist Paul Bion, who had served as the sculptor’s eyes and ears in the French capital for many years: "Of course the one thing on my mind, the terrible specter that looms up, is poor Bion's death; night and day, at all moments, it comes over me like a wave that overwhelms me, and it takes away all heart that I may have in anything. Today, however, I have had a kind of sad feeling of companionship with him that seems to bring him to me, in working over the head of the flying figure of the Shaw...

At the Twenty-seventh Street studio I've finished the nude of Sherman, and next week I begin to put clothes on him, and that, too, is progressing rapidly. Zorn, the Swedish artist, was with me all day Sunday, making an etching of me while the model rested; it is an admirable thing and I will send you a copy of it. The studio is once more in a fearful condition with the casting of the Logan, and the getting off the Puritan ready to photograph and cast for the Boston Museum and to send abroad to have reductions made." 11

With his distinctive leonine features, Saint-Gaudens was an attractive subject for Zorn to etch. As John H. Dryfhout notes in his catalogue raisonné, The Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens: "Saint-Gaudens was physically impressive... He was said to resemble Zeus." Author William Dean Howells, who was posing then for his own portrait by the sculptor, wrote, "His face was to me full of a most pathetic charm, like that of a weary lion, and, after our seeing him constantly, my daughter and I were finding sculptured lions all over Europe that looked like St. Gaudens." Zorn, too, was struck by the sculptor's fantastic visage and pronounced nose. He enjoyed etching portraits of his colleagues. His sketchbook from this period includes a red chalk drawing that captures Saint-Gaudens and his model. 12

The etching that Zorn produced in 1897 of Saint-Gaudens in reverse places the sculptor in the foreground, on the edge of the model's stand. His mass dominates the entire left side of the print. His long nose eclipses the right side of his face, and his left eye looks directly at the viewer. Saint-Gaudens's arched eyebrow accentuates the weariness with the world that he conveyed in the letter to Nichols. He leans over in fatigue, so that his arms rest on his thighs. In the background, his nude model is seen in repose, casually propped on one elbow. She leans diagonally in the same direction as the sculptor, with the trace of a smile on her lips. Her face has the freshness of youth–in marked contrast to Saint-Gaudens's. Zorn unites the figures by a series of closely spaced parallel lines moving in upward swirls that, along with Saint-Gaudens's stare, give the etching its intense energy.

By positioning the sculptor in the foreground, Zorn continues a compositional theme that he used in several earlier etchings and oil paintings: Zorn and His Wife, Albert Besnard and Model (1896), Self-Portrait with Model, and the painting Self-Portrait with Mother (1896). Like the Saint-Gaudens etching, each work places the male figure in front of the female, whether it is Zorn's mother, wife, or artist's model.

In his unpublished memoirs, James Earle Fraser, a beaux-arts-trained sculptor who assisted Saint-Gaudens, described Zorn's visits to Saint-Gaudens's Paris studio between 1898 and 1900 and offered insight into Zorn's etching of the sculptor and his model: "[Zorn] had come from Sweden on the King's yacht with the King and his retinue. He was a powerfully built man, rather short, with a pompadour haircut, wide eyes and a blonde mustache, and what more or less might be called a 'bullet' head. Usually in the morning he came in holding his hand to his head complaining about too much drink the previous night... Only lately a sculptor friend of mine said, looking at an etching which I have of Saint-Gaudens, 'I was working in the Saint-Gaudens studio when Zorn made that etching. I doubt that it took him more than an hour, and he did it directly on the copper. As a matter of fact he washed the acid on the plate in the studio sink.' While Zorn was in Paris, he came very often to the studio, and we enjoyed having him there. He was no bother to Saint-Gaudens. He worked mostly in our studio–he had the greatest facility in whatever he was working. He was engaging, pleasant and could speak English exceptionally well. That reminds me of what Gari Melchers at one time said to me about Zorn–'When it comes to etching,' Gari said, 'nearly everyone fumbles except Zorn.'" 13

Zorn claimed that etching was merely a diversion. He wrote in his memoirs: "Speaking of etchings, I devoted free moments, particularly evenings, to etchings, both reproductions of paintings and directly from life. I attached little importance to this pursuit, but was entertained by the surprises inherent in this game of chance, that lines that I incised with a steel needle on a treated black copper plate became light red against a dark background, and when printed would be black on a white field, and reverse to boot; it was like playing blindman's bluff, a game which delighted me then and still delights me now." 14

However, Zorn may have taken printmaking more seriously than he admitted, as illustrated by events surrounding another etching made in 1897. One of Zorn's most important patrons, Sir Ernest Cassel, had commissioned Saint-Gaudens about 1885 to do a portrait relief of Jacob Schiff's daughter and son. In turn, Schiff commissioned Zorn to etch a portrait of his father-in-law, Solomon Loeb. Zorn wrote in his memoirs that the Loeb commission "influenced my course in this medium... I made it while Schiff was in Europe. Both etcher and model were fascinated by the results, but when Schiff returned and saw it, he wrote to me, '[He] certainly does not deserve to be treated in such an evil way. Of the grand old man [you] made a hunch-backed Shylock.' I asked to have all fifty prints returned and that I would return the payment that the old man had given me. But I received no reply. I swore then to never take an order for an etched portrait. Many times I would have gladly done the same with painting in order to have a quite free hand, but of painting I was more dependent for my existence." 15

Karl Asplund, one of the early Zorn experts, related another incident that illustrates how highly Zorn regarded his etchings. While at home in Mora, Zorn, in a reflective mood, sat in front of his print cabinet that he had exclusively reserved for Rembrandt's etchings and his own. Zorn remarked that there were really only two great etchers. After a few moments, he corrected himself, commenting, "Only one etcher really." Asplund had no doubt that Zorn was referring to himself. 16

Zorn gave Daniel Burnham a copy of the etching of Saint-Gaudens and his model shortly after completing the work in February 1897. Burnham responded to Zorn on April 26: "Your superb portrait of Saint-Gaudens fascinates and moves me to a degree I have never experienced. You have increased my love for him and yourself. Thank you dear Zorn. You have sent into my abode a welcomed guest to enchant and dominate me. It is a soul speaking with a voice that will inspire me, even when all is silent. I can't express it and no one can, but the result of it is a quiet presence in my house, a living thing too, that can say things to me, things I have to hear." 17

In Zorn's etching of Saint-Gaudens, it has sometimes been assumed that the young nude reclining behind the sculptor was his model and mistress, Davida Clark. But by the 1890s, Augusta Saint-Gaudens had discovered her husband's affair. Clark and her son were exiled to Darien, Connecticut, where the sculptor surreptitiously visited them. The last work for which Clark posed was the James Garfield Monument that Saint-Gaudens completed in 1895, two years before the Zorn etching. Clark, well into her thirties by then, was too old to be the model in Zorn's print, and there is no physical resemblance. 18

The recent identification of the model as Harriette Eugenia Anderson has been reached by piecing together a number of surviving clues; knowledge that she posed for Saint-Gaudens in 1897 when the sculptor was designing the figure of Victory for the Sherman Monument and Zorn was making his etching, evidence that the sculptor presented a plaster bust to her as a gift that year, and several apparent references to her over the years in Saint-Gaudens’s writings.

For me, the discovery has been one of personal importance, inspiring my work on the connections between the careers of Saint-Gaudens and Zorn. Hettie Anderson, an African American, was a first cousin to my grandmother, Jeannie McCampbell Lee (1890-1887). Both women were from Columbia, South Carolina.

My grandmother recalled to family members how Miss Anderson had been an artists’ model in New York City and that she posed for the winged allegory of Victory for the Sherman Monument and for a gold coin designed by Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

When I first came across Zorn's etching of the sculptor and his model, I was intrigued by the masterful, yet seemingly spontaneous work by the Swedish artist.

Research has confirmed that the model in the etching and my grandmother's cousin were one and the same. 19

Saint-Gaudens must have been referring to her when he wrote to Rose Nichols on January 26, 1897, concerning his work on the Sherman Monument: "Next week I commence the nude of the Victory from a South Carolinian girl with a figure like a goddess." He also wrote a revealing passage in the first draft of his memoirs about a southern beauty: "I ...modeled the nude for the figure of Victory of the Sherman group from certainly the handsomest model I have ever seen of either sex, and I have seen a great many. The original plaster model was destroyed in the fire [1904]. The model was a young woman from Georgia [sic], dark, long legged, which is not common with women, and which if not exaggerated, is an essential requirement for beauty. Besides she had what is also rare with handsome models, a power of posing patiently, steadily and thoroughly in the spirit one wishes. She could be depended on; so much so that [John] La Farge has virtually taken her by the year, in order that he may have her when necessity requires. Having seen her the other day for the first time in eight years, I found her just as splendid as she was fifteen years ago when she was first drawn to my attention." 20

A bronze cast of the sculptor's portrait bust of Anderson, inscribed "to Hettie Anderson/Augustus Saint-Gaudens/1897," was included in the memorial exhibitions of Saint-Gaudens's work held in several cities after his 1907 death. The exhibition catalogue for the 1908 retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum in New York lists it as no. 92, "Sherman Monument: First Sketch for Head of Victory," and says it was "lent by Miss Hettie E. Anderson." Correspondence indicates that Anderson declined a request from Saint-Gaudens's family to obtain a cast of the bust, and thus it went unmentioned in future decades. 21

Art historian John Dryfhout rediscovered it when he reviewed the exhibition catalogues and letters and found negatives of the bust in the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Peter A. Juley and Son Collection of photographs of artists' work. He included an image in his important 1982 catalogue raisonné, listing it as the first study for the head of the Sherman Victory. Dryfhout's publication enabled researchers to bring the identity of the model in the etching into focus as well. 22

Stories that Davida Clark or Elizabeth Sherman Cameron, a niece of Sherman's and a portrait subject of Zorn's (1900), had modeled for Victory were largely dispelled. The importance of setting the record straight as to the model is heightened by the fact that Saint-Gaudens essentially reworked his Victory figure, and with slight changes, transformed her into Liberty on the 1907 twenty-dollar gold coin. Homer Saint-Gaudens, son of the sculptor, made a veiled reference to Anderson in the Reminiscences of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, the memoirs that he edited, when he noted that one of the coins his father designed was "modeled from a woman supposed to have Negro blood in her veins." 23

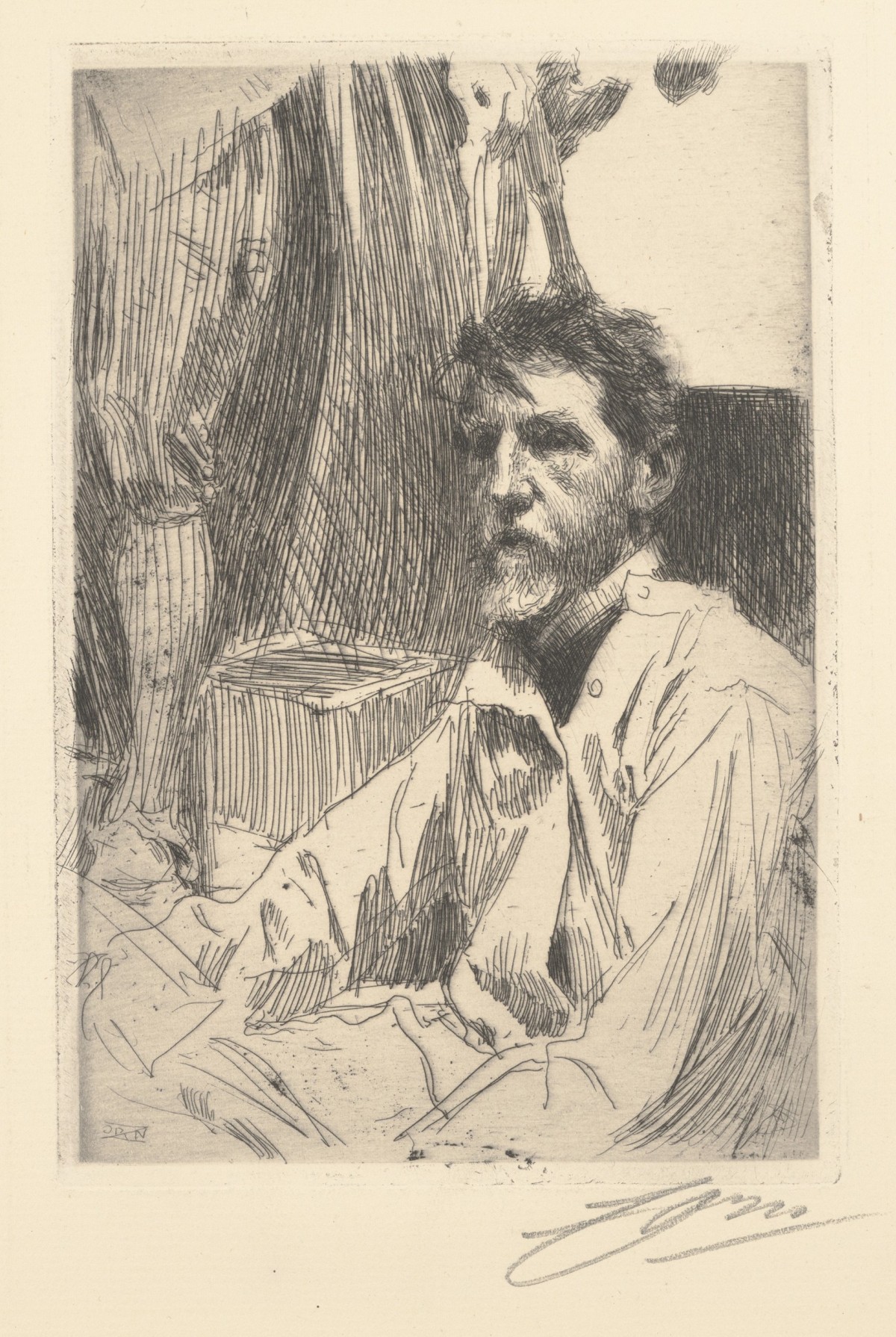

In 1898 Zorn, who used Saint-Gaudens's Left Bank studio on the rue de Bagneux when in Paris, etched a second portrait of Saint-Gaudens in his studio. The composition for this work included no nude lounging in the background, but the massive leg of Saint-Gaudens's Puritan (1883-86) to the sculptor's right. Perhaps as a result of placing the large statue in the background and positioning Saint-Gaudens upright rather than at a diagonal, as in the first etching, the composition lacks dynamism. The focus of the etching is the sculptor's face and its illumination of his character. Saint-Gaudens's gaunt features foreshadow the illness that would take his life in less than ten years.

In 1905, Zorn was again in America, and through the influence of his friend Secretary of State John Hay, he spent a day at the White House sketching Theodore Roosevelt who, at the time, was planning new designs for United States coins with Saint-Gaudens. Traditionally, presidential medals were produced by engravers at the mint.

Displeased with the quality of the work there, Roosevelt privately commissioned Saint-Gaudens to design a medal for his second inauguration in 1905, which Tiffany & Company struck in a limited edition of 3 gold and 125 bronze medals.

This commission led the president and sculptor, friends for some time, to discuss the possibility of improving the nation's coinage. Most of the coins in circulation were designed by Saint-Gaudens's nemesis Charles Barber, and the president and sculptor considered them mediocre. Saint-Gaudens and Roosevelt wanted America's coins to rival the artistry of the high-relief coins of ancient Greece, which both men admired. Roosevelt declared the project his "pet crime" and by January 1906 had directed Saint-Gaudens to proceed with designs for new twenty-dollar and ten-dollar gold coins. 24

Saint-Gaudens, ill and living full-time in Cornish, wrote to his former assistant Adolph Weinman on January 2, 1906: "Will you please mail the enclosed letter to Miss Anderson. Perhaps if she is posing for you, you might let her go for one, two or three days; I need her badly." Weinman promptly responded on January 5: "Replying to your letter... I wish to state that I have forwarded your letter to Miss Anderson." The destruction of the nude of Victory two years before in a fire at Cornish helps explain Saint-Gaudens's urgent need of Anderson as a model for the coin. He essentially transformed his Victory into the design of Liberty for the twenty-dollar gold piece. With a design of a flying eagle on the reverse, the coin is considered by many to be one of the most beautiful ever created. 25

On January 7, Saint-Gaudens wrote a second time to Weinman, asking for the loan of an Indian headdress. President Roosevelt wanted Liberty to wear an Indian crown of feathers on the twenty-dollar gold piece. Saint-Gaudens attempted to incorporate the headgear in the design of the coin, but later abandoned it as unsuitable to the circular format. Saint-Gaudens also asked Weinman for the loan of angel wings, which he had used with Victory, but like the headdress, found the wings difficult to integrate into the design of the twenty-dollar gold piece. 26

While designing the coins in 1906, Saint-Gaudens wrote in his memoirs (as mentioned earlier) about the development of Victory for the Sherman Monument. In commenting, "I found her [Miss Anderson] just as splendid as she was [before]," the sculptor appears to offer a professional observation. If Hettie Anderson traveled from New York to New Hampshire to pose again for Saint-Gaudens, it would not have been without precedent, as Allyn Cox, son of artist Kenyon Cox, said in a letter about the Cornish art colony: "One interesting fact that may have escaped the memory of others, is that professional models, girls who posed in the nude, used to come to Cornish for the summer, to work in the various studios." 27 Given Saint-Gaudens's state of health, the pressures of completing commissions, and the watchfulness of his wife, it is unlikely that Hettie Anderson and Saint-Gaudens saw each other in 1906 during a casual meeting or by chance. On August 14, 1906, Saint-Gaudens wrote to Zorn from Cornish: "Rublee has told me of seeing you in Paris, which brings many memories, not least of which is that of you. I have you more in mind and your friendship more at heart than you would imagine from my silence, but, well------, you know. Your Masterpiece of me [the etching] hangs in my studie [sic] and is a constant pleasure; I wish I could really repay you for it. You know I promised you a reduction of the nude of the Goddess-like Miss Anderson, but... it was destroyed in the fire.... In its stead, I send you the bronze casting of my study of the head of Victory from the Sherman group [second version, 1902-03, after a different model] and which will leave in a day or two by express (all charges prepaid) and which you should receive in a month or so. I hear good reports of you and your wife; Mrs. Saint-Gaudens and I send her our love and much of that." 28

Zorn replied on September 22: "Your heart and friendship is the same old good one and God bless you! We do not excel in writing neither of us and our mission in life is indeed another but I am sure you know my sympathy has been with you through all your troubles and the hope to get you strong and vigorous and back to your art again, an art that in my mind is the monument of our time. And you dear boy making such a magnificent gift–it has not yet arrived but I expect it will each day. Now goodbye [and] God bless you again and again and again." 29

When the bust arrived, Zorn wrote from Mora to his ailing friend on December 14: "I just returned from a busy sojourn in Stockholm and find your beautiful bronze on my mantlepiece and God knows my heart beats faster whenever I look upon the beautiful head which brings so many dear souvenirs to my mind of you and the happy hours I have spent in your society. And what could be happier [than] to be remembered by the one to whom one looks up to not only as a sincere friend but as a big creator for centuries. Strange enough came at the same time a souvenir from Rodin, also a bronze, The Creator's Hands I think he calls it–a very beautiful thing, but the two touch me very differently. You understand why. I wish there was a chance of seeing you soon. The other day I offered a friend a trip to your side of the water, but I got home here [and] Mrs. Zorn tells me that I have already offered to take her to Paradise (somewhere in Asia Minor) this spring. So now I don't know how to get split in two. My inclination is westward and then I shall hope to shake hands with my dear friend St. Gaudens. God Bless you and aurevoir." 30

The two friends never met again. Saint-Gaudens succumbed to cancer on August 3, 1907, just before his gold coins were placed in circulation.

Zorn immediately wrote to Isabella Stewart Gardner: "I have just had [a] month cruise on the Baltic on my little yacht. Plenty [of[ bad weather. Just in town to fetch my mail. Afful [sic] news that St. Gaudens is no more!" 31

With the sculptor's death, his family, particularly Augusta Saint-Gaudens, Homer Saint-Gaudens, and Rose Nichols, immediately began to protect his posthumous reputation.

When the architect Stanford White had been murdered the year before by the jealous husband of a young woman with whom White had had an affair, the public was outraged by revelations of his lifestyle. The Saint-Gaudens family made every effort to distance the sculptor from the scandal. Since he and White were closely linked personally and professionally, they were especially anxious to obscure his affair with Davida Clark.

The family also wanted to obtain copyrights for the sculptor's work to earn income for them. Homer Saint-Gaudens wrote to Hettie Anderson less than a year after Saint-Gaudens's death, asking for the right to replicate the plaster bust his father had made of her in 1897. She replied on January 13, 1908: "I rec'd your letter... asking me to loan, for the purpose of duplicating, the study of the head made from me by Mr. Saint-Gaudens, when he first began the Sherman group. When Mr. Saint-Gaudens gave me the head he had a small pedestal made with it, and he said: 'Some day this may be valuable to you, and if you will let me take it abroad and have it put in bronze for you, it may be worth a great deal of money.' I thanked him, but told him that I thought I would take it then–which I did. Valueing [sic] it as I do, and knowing as I do that it is the only one in existence, in that state–I am not willing to have any duplicate made of it, for any purpose whatever. You will realize that if I were to allow it to be copied it would greatly depreciate its value–innumerable copies could be made of it. In my possession it is the only one and therefore the more valuable." 32

As a result of her refusal to cooperate, Anderson was written out of Saint-Gaudens's life and work–a history that Homer Saint-Gaudens largely controlled. Even though Anderson had loaned her bust to the 1908 memorial exhibition in New York and was acknowledged in the catalogue, Homer Saint-Gaudens eliminated the sculpture from a "complete" catalogue of his father's work that appeared in his memoirs. In addition, instead of using his father’s title, Reminiscences of an Idiot, for publication of the autobiography, he substituted his own more dignified one, The Reminiscences of Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Burke Wilkinson, a Saint-Gaudens biographer, wrote: "Self-told lives can conceal as well as clarify." Wilkinson identified the family's role in editing of the memoirs: "They made it their task to see that the final product was completely sanitized and quite bloodless." 33 The opening chapter dealing with Saint-Gaudens’ childhood in New York, his apprenticeship, and his student years were left much as he wrote them and made for interesting reading. However, Homer Saint-Gaudens censored his father's professional years, and even interjected lengthy, tedious passages of his own.

Etching on paper, 25.2x32.4 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

After Saint-Gaudens's death, there was a surge of interest by the public the following year as to who had posed for the gold coins. Because the family was eager to deflect attention from Saint-Gaudens's models, Homer Saint-Gaudens eliminated from the memoirs any mention of Clark and her son, and also Hettie Anderson. He wrote, "In reality, [on the coins] as in all examples of my father’s ideal sculpture, little or no resemblance can be traced to any model, since he was always quick to reject the least taint of what he called 'personality' in such instances." 34

In addition, referring in the memoirs to the relationship that his father had enjoyed with Anders Zorn, Homer Saint-Gaudens quoted the letter his father had written to Rose Nichols mentioning Zorn’s etching with model ("Zorn... was... making an etching of me while the model rested"). Instead of reproducing that etching for the memoirs, however, he used the second etching of his father seated before The Purtian. Homer Saint-Gaudens further obfuscated the existence of the first etching by writing that "Zorn... made an etching of Saint-Gaudens," rather than acknowledging that Zorn made two etchings of his father. Nichols also deliberately chose the second etching for reproduction when she published a collection of letters that her uncle had written her in McClure’s Magazine in 1908. 35 It is, of course, the earlier little etching, done rapidly on Sunday in February in a New York studio, that not only provides a clue to the identity of the model, Hettie Anderson, but also helps illuminate the close friendship and professional ties of Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Anders Zorn.

Notes

I am indebted to Birgitta Sandström, director of the Zorn Museum, Mora, Sweden, for allowing me access to the museum’s archives and for her help in my research. I am also grateful to John Dryfhout, director of the Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site in Cornish, New Hampshire, for his generous assistance. The late Burke Wilkinson offered encouragement and suggestions regarding my research into the lives and work of Saint-Gaudens and Zorn.

1. The etching is listed as "extremely rare" in Zorn Engravings: A Complete Catalogue, preface by Hans Henrik Brummer (Uppsala: Hjert and Hjert, 1980), no. 74. There are three previously published catalogues of Zorn’s etchings: Fortunat von Schubert-Soldern, Das Radierte Werk des Anders Zorn (incomplete) (Vienna: Gesellschaft för Verielfaltigende Kunst, 1905); Loys Delteil, Le Peintre Graveur Illustré, vol. 4 (Paris: Chez l’auteur, 1909); and Karl Asplund, Zorns Graverade Verk (Stockholm: Bukowskis Konsthandel, 1920). The Asplund catalogue was published in English as well as in Swedish in 1920 and was reproduced by Alan Wofsy Fine Arts (San Francisco) in 1990. I have located eight of Zorn’s etchings of Saint-Gaudens and his model in American collections. The same number are known to exist in European collections. On the recent exhibition in France that included the etching, see Augustus Saint-Gaudens 1848-1907: A Master of American Sculpture, ex. cat. no.3 (Toulouse, France: Musée des Augustins, 1999), p. 102. For my research into the identity of Anderson, see William E. Hagans' Who Really Modeled for Saint-Gaudens’s $20 Gold Coin? The Case for Hettie Anderson Coins (November 1998): 42-87.

2. Zorn’s comment about associating with Americans in Paris is found in his memoirs, Anders Zorn: Självbiografiska anteckningar, ed. Hans Henrik Brummer (Stockholm: Bonniers, 1982), p. 71. Translations from Zorn’s memoirs are provided by the author. Zorn and Saint-Gaudens may have met in Paris in June 1889, when the sculptor attended the Exposition Universelle there.

3. The papers of John White Alexander, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., reel 1727, frame 167.

4. James Waddell Alexander was the father-in-law of John White Alexanders. The two men shared the same last name and initials. Zorn made an etching of John White Alexander in 1893. The Schiff connection was through Emma Zorn’s uncle Henrik Davidson, who introduced the Zorns to Sir Ernest Cassel, Jacob Schiff’s childhood friend in Germany. Frederick Keppel was Zorn’s principal graphics dealer in America. Zorn etched Keppel’s portrait in 1898. On Zorn’s etching of Henry Marquand, see Elizabeth Broun’s The Prints of Anders Zorn: Catalogue (Lawrence, Kans.: Spencer Museum of Art, Univ. of Kansas, 1979), p. 55.

5. Zorn, Självbiografiska, pp. 78, 82-83.

6. Augustus Saint-Gaudens, The Reminiscences of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, edited and amplified by Homer Saint-Gaudens (New York: Garland Publishers, 1976), vol. 2, p. 116.

7. On Zorn and sculpture, see Birgitta Sandström, Skulptören Anders Zorn (Mora, Sweden: Zornsamlingarna, 1999). Along with the two etchings Zorn made of Saint-Gaudens, as well as the previously mentioned etching of Auguste Rodin, he also etched portraits of sculptors Per Hasselberg in 1891 and Paul Troubetzkoy in 1908 and 1909. Zorn worked closely with Swedish sculptor Christian Eriksson and associated in Paris with Finnish sculptors Emil Wikström and Ville Vallgren.

8. Art Amateur (December 1893): 3. Emma Zorn to Henrietta Meyerson Lamm, 18 October 1893 (translation by author), Zorn Museum Archives, Mora, Sweden. On Burnham, see Charles Moore’s Daniel Burnham, Architect, Planner of Cities (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1921, vol 1, p. 47.

9. For Saint-Gaudens’s Columbian presentation medal, see William E. Hagans, Columbian Expo Medal Source of Controversy, Numismatic News, 4 May 1993.

10. Zorn, Självbiografiska, p. 64. On Zorn’s second trip to America, he painted portraits of Adolphus Busch, Lilly Anheuser Busch, Carrie Casey Nugent, Lucy Turner Joy, and Dr. William Taussig while in St. Louis. In Chicago, Zorn painted portraits of William Deering and Barbara Deering; and in New York, Edward Rathbone Bacon and Virginia Purdy Bacon. Etchings from the trip include those of Mrs. Potter Palmer, Mrs. Charles Nagel, Solomon Loeb, Edward Rathbone Bacon, as well as Saint-Gaudens and model.

11. Saint-Gaudens to Rose Nichols, 17 February 1897, Saint-Gaudens, Reminiscences, vol. 2, pp. 119-21.

12. John H. Dryfhout, The Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens (Hanover, N.H.: Univ. of New England, 1982), p. 37. William Dean Howells’s remarks are found in Saint-Gaudens’s Reminiscences of Saint-Gaudens, vol. 2, p. 65. The red chalk sketch of Saint-Gaudens and model is reproduced in Erik Forssman’s Tecknaren Anders Zorn (Stockholm: Bokförlaget Natur och Kultur, 1959), pp.49, xi. The National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., has in its possession a charcoal drawing of the same subject, signed “Zorn.”

13. James Earle Fraser and Laura Gardin Fraser Papers, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, draft, box 61, pp. 3-4, Syracuse Univ. Library, Manuscript Collections, New York. I am indebted to John Dryfhout for bringing Fraser’s memoirs to my attention. A similar Fraser manuscript in the Saint-Gaudens Papers, Dartmouth College Library, Hanover, N.H., is more heavily edited and does not refer to Zorn’s etching of Saint-Gaudens’s portrait in New York City.

14. Brummer, Zorn Engravings, p. 9.

15. Zorn, Självbiografiska, p. 94.

16. Brummer, Zorn Engravings, p. 11. Asplund related this story to Brummer in 1975. Zorn had an extensive collection of Rembrandt etchings, which are now part of the collection of the Zorn Museum; see Rembrandt etsningar ur Zorns samling, with a forward by Erik Forssman (Malung, Sweden: Malungs boktryckeri AB, 1964), a catalogue of an exhibition of etchings at the Zorn Museum. Asplund, in addition to his catalogue of Zorn’s etchings, published a biography of Zorn, Anders Zorn: His Life and Work (London: Studio, 1921).

17. Daniel Burnham to Anders Zorn, 26 April 1897, Zorn Museum Archives. Burnham wrote several other panegyric letters to Zorn after the Swede painted the architect’s portrait in 1899. These letters are also in the Zorn Museum Archives.

18. Elizabeth Broun noted in the catalogue for the 1979 exhibition of Zorn etchings at the Spencer Museum of Art, the first extensive showing of the artist’s work in America since the 1930s: "The seductive pose of the model and the psychological intensity of the portrait of Saint-Gaudens... suggest that this etching may show the sculptor with Davida Johnson Clark, the beautiful young model by whom he had a child"; see Broun, Prints of Anders Zorn, p. 62. It was not until 1982, with the publication of Dryfhout’s catalogue raisonné of the sculptor, that a picture of Davida Clark was published.

19. When my mother died in 1988, it was my sister, Jeannie Derricotte, who, while we looked through family photographs, recalled that Anderson was Saint-Gaudens’s model. According to an aunt who lived in New York City, my grandmother would come from her home in Tuskegee, Alabama, to stay with her and visit Anderson. My grandmother told her family that Anderson had posed for Saint-Gaudens’s Victory and for a gold coin. I have been unsuccessful in finding a date of death for Hettie Anderson.

20. The earliest known mention of Hettie Anderson in connection with Saint-Gaudens is found in Stanford White's daybook; see correspondence book 13 (15 March 1895-11 July 1895), Stanford White Collection, Avery Library, Columbia University, p. 176. On the letter from Saint-Gaudens to Rose Nichols, 26 January 1897, see Rose Nichols, ed., "Familiar Letters of Augustus Saint-Gaudens," McClure’s Magazine 31, no. 6 (October 1908), p. 606. Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s comments about his model are found in The Reminiscences of an Idiot, the unpublished first draft of his memoirs, Saint-Gaudens Papers, Dartmouth College Library, pp. 109-109a.

21. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catalogue of a Memorial Exhibition on the Works of Augustus Saint-Gaudens (New York, 1908), no. 92.

22. Dryfhout, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, p. 219. The bust of Hettie Anderson is catalogued as number 164. Dryfhout notes that the sculptor began work on Victory in January 1897. The letter from Hettie Anderson to Homer Saint-Gaudens, 13 January 1908, is found in the Saint-Gaudens Papers, Dartmouth College Library.

23. Saint-Gaudens, Reminiscences of Saint-Gauden, vol. 2, p. 332.

24. John Hay was an old friend of Zorn’s. The two met in London in 1882, where Zorn painted a watercolor portrait of Hay’s wife. Saint-Gaudens had created the Adams Memorial for Hay’s close friend Henry Adams. Zorn etched Hay in 1904 during the same trip that he etched President Roosevelt.

25. Saint-Gaudens to Weinman, 2 January 1906; Weinman to Saint-Gaudens, 5 January 1906; Saint-Gaudens Papers, Dartmouth College Library. Regarding Liberty on the twenty-dollar gold piece, Dryfhout wrote, "Saint-Gaudens no doubt was inspired by his Victory in the Sherman Monument... There is a marked resemblance to the classical figure of Nike or Victory, holding aloft a palm leaf and striding ahead of the equestrian Sherman"; see Dryfhout, The 1907 United States Gold Coinage, rev. ed. (Barre, Vt.: Northlight Studio Press, 1996), p. 1. Cornelius Vermeule wrote, "The double-eagle [reverse] is perhaps the most majestic coin ever to bear our national imprint. The Liberty striding forward is as grand in miniature as the Hellenistic Victory of Samothrace on a heroic scale"; see Vermeule, Numismatic Art in America: Aesthetics of the United States Coinage (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard Univ., 1971), p. 115.

26. Saint-Gaudens to Weinman, 7 January 1906; Saint-Gaudens Papers, Dartmouth College Library.

27. Allyn Cox to James Farley, n.d., Saint-Gaudens Papers, Dartmouth College Library.

28. Saint-Gaudens to Zorn, 14 August 1906, Zorn Museum Archives. The bust Zorn received, which was clearly fashioned after a different model, remains at the Zorn Museum, Mora. There have been a number of theories about the identity of the model for this second study. The most likely may be Alice Butler, a young woman originally from Windsor, Vermont, who also modeled for the ten-dollar gold piece. See Louise Hall Tharp, Saint-Gaudens and the Gilded Era (Boston: Little, Brown, 1969), note 11, p. 395, with a photo of Butler from the Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site on p. 362.

29. Zorn to Saint-Gaudens, 22 September 1906, Saint-Gaudens Papers, Dartmouth College Library.

30. Zorn to Saint-Gaudens, 14 December 1906, Saint-Gaudens Papers, Dartmouth College Library. Rodin served on the committee of Zorn’s retrospective exhibition at the Durand-Ruel Gallery in Paris, 1906. While in Paris, Zorn etched Rodin’s portrait. In thanks, Rodin sent Zorn a version of his bronze sculpture Le main de Dieu (The Hand of God) and four drawings of nudes, which are in the collection of the Zorn Museum.

31. Zorn sent flowers to Saint-Gaudens’s funeral; his signed card is found in the Dartmouth College Library collection. Zorn to Mrs. Gardner, 10 August 1907, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Correspondence, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

32. Hettie Anderson to Homer Saint-Gaudens, 13 January 1908, Saint-Gaudens Papers, Dartmouth College Library. Anderson’s fear of the duplication of her bust was not unfounded. The second head of Victory, the version Saint-Gaudens sent to Zorn, was reproduced at least twenty times. It is unclear under what circumstances Anderson’s bust was cast into bronze for exhibition in the retrospectives.

33. Burke Wilkinson, Uncommon Clay: The Life and Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1985), xi.

34.Saint-Gaudens, Reminiscences of Saint-Gaudens, vol. 2, p. 332. On reporters pursuing the Saint-Gaudens family after the sculptor’s death, curious about who modeled for the two gold coins, see Vexes Son of St. Gaudens,” New York Times (21 September 1907), p. 1.

35. Rose Standish Nichols, ed., Familiar Letters of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, McClure’s Magazine 32, no. 1 (November 1908), p. 12. Homer Saint-Gaudens used the same etching in his father’s Reminiscences (vol. 2, p. 118).