Anders Zorn in America

by Willow Hagans

Scandinavian Review, autumn 2019

Between the years 1893 1911, this great Swedish artist made seven extended trips to America, painting and etching more than 100 prominent Americans, including three presidents, important industrialists, and Gilded Age society members.

Anders Zorn, one of the world's most famous living artists at the turn of the 20th century, was born in Sweden in 1860 and died in 1920, making next year the 100th anniversary of his death. He started out as a watercolorist, later turned to etchings (almost 300 of which contributed to the revival of that art form) and finally to painting, most notably, perhaps, for the vigorous style of his paintings of peasant girls bathing. He was an outstanding portrait painter, vying for contemporary fame with John Singer Sargent. In America, Zorn primarily painted portraits of the rich and famous.

Unlike other European artists who painted portraits in the United States, Zorn did not limit his trips to the East Coast, but spent considerable time in Chicago, St. Louis, and Pittsburgh, and traveled as far as California,, Florida, Texas, Louisiana, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Mexico and Cuba.

Since the late 1980s, my late husband Bill and I have been engaged in a mutually inspired research and documentation of Zorn's works created in the States and we have had an ongoing relationship with the Zorn Museum in Sweden. Our efforts culminated a few years ago with the publication of our book, Zorn in America: A Swedish Impressionist of the Gilded Age, by The Swedish-American Historical Society. The book is now in its second printing.

Zorn loved America and related his humble peasant roots in north-central Sweden to his appreciation of his host country. He wrote in his memoirs:

I get on well in America and with Americans. Their frank, straight-forward manner suits my nature. I've never really been able to stand our urban Europeans' ceremonious style and artificial customs. When I first came out of Dalarna, I learned quickly that everything I knew and valued was considered nothing, and that one should never tell the truth in polite society... But the only rules of conduct that were so severely impressed on me by my grandfather from my earliest childhood were not so tricky; faithfulness, being true to one's word, honesty and punctuality, virtues I discovered were unnecessary in the cities of Europe. Why was I more than other foreigners during (my visits to America) closest to the elite of America and introduced in all the clubs? Everywhere I go, I ascribed this to my grandfather, the splendid old Mora peasant who raised me until I was 12. Over there (in America), when they say “He’s all-right,” all door opens to foreigners, which Europeans cannot understand. Openness, honesty, straightforwardness, punctuality, these things are included in the testimonial "He's all-right."

Despite the fact that Zorn was illegitimate and never met his German

father, his talent rapidly propelled him to success as a watercolorist. In London,

he painted portraits of American geologist Clarence King (1842-1901), a

close friend of Henry Adams (1838-1918) and John Hay (1838-1905), and he

painted Hay's wife Clara Stone Hay (1849-1914).

He also made portraits of

Clarence Barker (d. 1896) and his sister Mrs. Walter Bacon (d. 1919), both

grandchildren of Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1877). At St. Ives, with the help

of American artist and member of The Ten, Edward Simmons (1852-1931),

Zorn switched to oils, and his first official effort in the new medium, Fisher-man at St. Ives, was purchased by the French government.

After several years of success in Paris, Zorn was named Swedish com

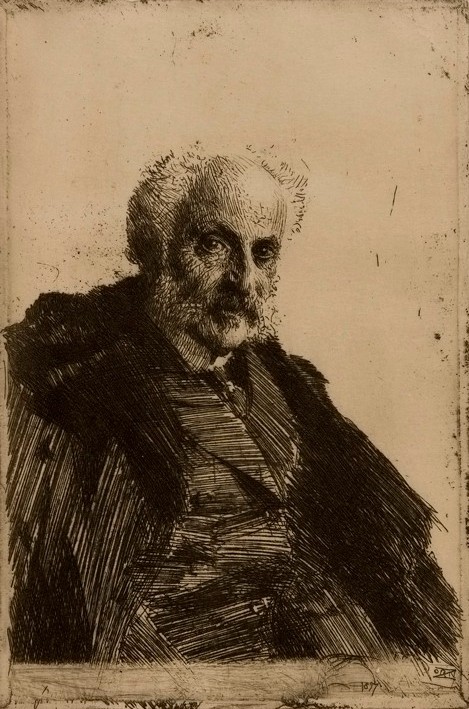

missioner of art for the Chicago World's Fair in 1893. His first commission

in America was to etch the portrait of Henry Marquand (1819-1902), the

president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Marquand was a businessman

who left important Old Masters to the museum.

The Zorns were introduced

to New York society by James Waddell Alexander (1839-1915), president of

the Equitable Insurance Company.

Zorn was good friends in Paris with the man's son-in-law, painter John White Alexander (1856-1915).

Writing to her mother, Emma Zorn noted that she was eating oysters twice a day and that they come in close contact only with the upper class, which, according to Emma "was the same everywhere." As enthusiastic as Zorn was about America, Emma was skeptical, writing to her mother that in "free America" women were restricted to establishments with signs reading "Ladies and Gents Dining Room,” while the men could go anywhere. She wrote to her mother that Americans lacked refinement but that she admired their innovative spirit: “It is not worth holding Americans in contempt. They are certainly full of new ideas and fortunate to have the money to realize them. I believe they are people of the future, not only in business but in artistic considerations.”

Traveling to Chicago in the spring of 1893, Emma was even less impressed by the Midwest than she was with New York. Opening day of the fair in the "White City," however, won her over: “The sight of the numerous white buildings against the water and the great crowd of people was impressive. We had exceptionally good seats and were able to see the president, Mrs. (Potter) Palmer and all the people of society. When Grover Cleveland declared the exhibition open, he pressed an electric button and at the same moment all the flags unfurled, guns thundered, and—as is typically American—steam whistles from boats, machines and locomotives in a radius of miles began to wail—a grand, if not musical, impression."

Zorn enjoyed tremendous success in Chicago and raised the profile of Swedish art in America. He sold all of his works, despite the financial panic of 1893, and the Art Amateur declared, "We believe that if a vote were taken, Mr. Zorn would turn out to be the most popular artist among artists at the World's Fair." He sold his Waltz to George Vanderbilt (1862-1914) and hangs today at the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina. Zorn's Parisian Omnibus was purchased by Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840-1924) of Boston. At their first meeting, Mrs. Gardner declared to Zorn that they would either become great friends or bitter enemies. Fortunately for Zorn, the first prediction prevailed, and Mrs. Gardner went on to become one of his greatest patrons.

For Zorn’s birthday party in Boston on February 18, 1894, Mrs. Gardner invited Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924) to perform at her Beacon Street home, and in October of the same year, the Zorns spent a month as the Gardners' guests at Palazzo Barbaro in Venice. It was there that Zorn painted a radiant portrait of his hostess stepping from over the Grand Canal. The portrait today hangs in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston.

Charles Deering (1852-1927) was an enthusiastic amateur artist who would become the first chairman of the International Harvester Company. Meeting Zorn at the fair, he invited the artist and his wife to stay at his lakeshore home in Evanston for the summer. Deering would, together with Mrs. Gardner and Sir Ernest Cassel (1852-1921), become a close friend and patron of the Swede.

While in Evanston, Zorn, an avid equestrian, fell from a horse and dislocated his right shoulder. This occurred just before receiving the commission to paint Mrs. Potter Palmer (1850-1918), head of the Board of Lady Managers for the fair. Handling the large canvas and painting with his left hand were challenges, but the portrait was a success. Today the portrait is in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Returning to New York in the fall of 1893, Zorn painted a number of portraits, including that of Frieda Schiff, later Mrs. Felix Warburg (1876-1958), whose mansion at Fifth Avenue and 92nd Street is today the Jewish Museum. Her portrait by Zorn is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum. Returning to Paris in the spring of 1894, Zorn wrote to Mrs. Gardner that all of Chicago was in Paris. He painted Maria Sheldon Scammon (d. 1902), benefactor of the Scammon Lectures at the Art Institute of Chicago, and William Ogden III, grandson of Chicago's first mayor. Zorn also painted a portrait of Halsey C. Ives (1847-1911), founder of the St. Louis School and Museum of Fine Arts.

During his second trip to America in 1896-1897, Zorn painted a portrait of Adolphus Busch (1839-1913) in St. Louis. He was the co-founder of Anheuser Busch Brewing Company. In New York Zorn etched a portrait of Solomon Loeb (1828-1903), co-founder of Kuhn, Loeb and Company, a prominent Wall Street bank. The commission was from Jacob Schiff (1847-1920), a member of the firm and Loeb's son-in-law (and father of Frieda Schiff Warburg). Schiff, described as “the ablest of bankers” and “a tyrant," was offended by what he described as Zorn's portrayal of “this grand old man” as a “Shylock.” As a result, Zorn wrote in his memoirs, “I swore then to never again take an order for an etched portrait. Many times I would have gladly done the same with painting in order to have a quite free hand, but of painting I was more dependent for my existence.”

While in New York, Zorn renewed his friendship with American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848-1907). The Swede often came to the sculptor's studio and Homer Saint-Gaudens (1880-1958), the sculptor's son, wrote, "Zorn was always a favorite with my father and furnished many anecdotes. The last of them was especially liked because of its illustration of the casual way Zorn took himself. The artist appeared at the studio one morning to sit for some minutes, as was his custom while my father worked. 'What are you doing?' asked my father, finally breaking the pause without turning around. 'Going to Europe in twenty minutes,' breathed Zorn without looking up. And he went.”

In February of 1897, Saint-Gaudens was working on his Sherman Monument, destined for Fifth Avenue and 59th Street. The work included the allegorical figure of Victory, and the model, Hettie Anderson (born in 1873), was in the studio one day during one of Zorn's visits. Instead of sitting quietly, Zorn sketched, then etched, the sculptor with the model resting. Saint-Gaudens later described Miss Anderson as being "dark, long legged, certainly the handsomest model I have seen of either sex, and I have seen a great deal." The sculptor also called her "the goddess-like Miss Anderson" in a letter he wrote to Zorn in 1906.

In Paris, Zorn became "dangerously attracted" to Emily Bartlett (b. ca. 1871), wife of American sculptor Paul Wayland Bartlett (1865-1925). The Swede had painted a portrait of Mrs. Bartlett in Paris, but the picture was destroyed. When Emily and others visited Mora in 1898, while the Bartletts were divorcing, Zorn etched Emily engaged in his favorite pastime, billiards. Emily's presence in Mora caused tension in the Zorn’s relationship. Anders was forced to choose between the women, and he chose to stay with Emma.

On Zorn's third trip to America in 1899, Colonel Daniel Lamont (1851- 1905) arranged for Zorn to travel to Princeton to paint and etch Grover Cleveland (1837-1908). The former president had retired from politics after serving two terms in the Oval Office. Cleveland said that he would rather go to the dentist than to have his portrait painted. Zorn was introduced as the dentist. The artist wrote:

Cleveland greeted me humorously and sympathetically and we were good friends. Lamont stayed and talked with my victim during the first session, and soon I was able to develop my composition. During work time, I sought to interest the old man by holding the picture at different angles and asking his advice; if he thought I ought to make the line longer there or get more of the color here or there. Then I noticed something was awakened within him, which had previously been dormant—what constitutes art—so he could say, 'I believe you are correct. The line should be moved further there,' etc. He was to the end more interested in my work than others I've painted.

One morning, Cleveland asked Zorn who was the best painter of women. The Swede replied that John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) was his choice. Zorn was excited to learn that Grover Cleveland chose him to paint a portrait of his young wife, Frances Folsom Cleveland (1864-1947). John H. Drythout wrote of the former First Lady: "Tall and graceful with beautiful dark eyes, she became the most charming woman seen in the White House since Dolly Madison." Zorn wrote: "God, how stately and beautiful, and those arms, that neck, that bust worthy to be kissed by a thousand lips and now scarcely to be revealed to mortals."

Zorn wrote in his memoirs: "Well, after three calm and pleasant weeks with the Clevelands and other friends in the university town, I went to New York where I had dinner at Edward Rathbone Bacon's (1846-1915) and met a man who would cause me unpleasantness and disruption in my life."

The man was Henry Clay Pierce (1849- 1927), a St. Louis millionaire whose company was described as "one of these numerous businesses affiliated with the Standard Oil Company no man knoweth precisely how."

Pierce ordered three portraits for $12,000 and Zorn went to St. Louis to fulfill the commission.

Pierce was difficult from the start and treated Zorn like a day laborer. When Pierce refused to pay for the three portraits, Zorn filed a lawsuit against the millionaire. For over a year the case was widely followed in the American press, with Zorn receiving much sympathy from the artistic community.

Just before the trial, which Pierce and his team of lawyers constantly fought to delay, the millionaire backed down and settled out of court—with interest.

In contrast to St. Louis, Zorn enjoyed his time in Evanston (1899), where he painted architect Daniel Burnham (1846-1912). Along with a brilliant career in Chicago transforming the city's skyline, he had been in charge of architecture for the "White City” at the Chicago World's Fair. During Zorn's fourth trip to America 1900/1901, he etched a brilliant portrait of Senator Billy Mason (1850-1921) of Illinois. He also celebrated his victory over Pierce in New York with friends. Isabella Stewart Gardner came from Boston, Charles Deering from Chicago and his lawyer during the case, Charles Nagel (1849-1940), came from St. Louis. He painted a portrait of Nagel at the time. Nagel would go on to become part of President William Howard Taft's cabinet.

On Zorn's fifth trip to the United States in 1904, he traveled with Charles Deering to California to paint Richard T. Crane (1831-1912), of the plumbing empire, and his young bride. In Washington, D.C., Zorn etched a a portrait of his old friend Secretary of State John Hay. Hay arranged a meeting with President Theodore Roosevelt and the result is a dynamic portrait. Zorn also painted Congressman Robert Hitt (1834-1906), which prompted Henry Adams (1838-1918), never one to easily dispense compliments, to declare that Zorn was now "number one" in portrait painting. Adams reported that Zorn's Hitt contained more life than Hitt the man. Zorn finished this fifth trip at the St. Louis World's Fair, where his works were well received. While in St. Louis, he painted a portrait of Robert Brookings (1850-1932), founder of the Brookings Institution.

The sixth trip to America in 1907 saw Zorn swear off portrait painting in favor of a pleasure trip to Florida, Cuba and Mexico. He rounded out the trip with leisurely stops in San Antonio and New Orleans. While in St. Louis, Zorn stayed with Halsey C. Ives, who was in charge of art at both the Chicago World's Fair and the St. Louis World's Fair. The artist made his way back to Europe via Boston and New York, where he saw many old friends.

Zorn's seventh and last trip to America occurred in 1911, nineteen years after his first trip. He was asked for the third time to sit on the jury of the international art exhibition at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh. As with the previous trip, Zorn did not intend to paint portraits, but a call from Washington changed his plans. He was asked to paint President William Howard Taft (1857-1930) for the White House.

Marvin Sadik, former director of the National Portrait Gallery, wrote of the work:

Zorn's portrait of Taft executed in the Blue Room in 1911, is the likeness of a man burdened by the weight of body and mind. It was done at a time when his subject was becoming deeply concerned about the loyalty of old friends in the face of former President Roosevelt's impending decision to challenge him for the Republican nomination at the party's convention the next year. “The president is so weary that it shows in his face,” Zorn told Taft's secretary of commerce and labor, Charles Nagel. "Can't you come over and talk to him so I can paint him as really is?” Nagel tried, but Taft remained unchanged, and Zorn's virtuosity and insight left us one of the most powerfully truthful of all presidential portraits.

Zorn’s busy week in Washington included not only the portrait of the president, but that of Vice President James Schoolcraft Sherman (1855-1912), who died the following year, Sena- tor Nelson W. Aldrich (1841-1915) and, for Mrs. Gardner, Assistant Secretary of the Treasury A. Piatt Andrew (1873-1936). When the younger Andrew predicted the Panic of 1907, Aldrich elicited his help, and together with Paul Warburg (1868-1932), the men established the framework for legislation that created the Federal Reserve System (1913). In New York, Zorn painted a portrait of Andrew Carnegie before departing for the last time to Europe from North America.

Having spent a life in nearly constant motion, Zorn, the quintessential internationalist, felt the isolation that World War I imposed upon him and others, and it affected him profoundly. Fortunately, he was able to keep in touch with his many American friends through his relationship with U.S. Ambassador to Sweden Ira Morris (1857-1942). Over a three-year period during the war, Zorn painted Morris, his wife and their daughter Constance.

After Zorn's death in 1920, his work remained before the American public through a number of exhibitions that continued well into the 1930s. A large retrospective exhibition of the artist's work traveled to Pittsburgh in 1924. Emma Zorn wrote to Isabella Stewart Gardner in 1920, "It might interest you to hear that we have followed your good example in donating your collections to the state.”

The Zorn Museum was established in Mora in 1939. Zorn took

pride in the fact that presidents Harrison, Cleveland, Teddy Roosevelt and

Taft told him that Swedes were the backbone of America. Nearly 25 percent of

the population of Mora emigrated to the United States in the latter half of the

19th century.

In this singular Swede, we find a man, Anders Zorn, who totally

embraced his Swedish roots and worked hard to preserve peasant traditions

while maintaining a deep love for Americans and America.